In this essay I would like to give a proof of a certain definition of truth. Let us refer to this definition as H. But what would this kind of proof even look like? Well, it is an argument for something, so there should be a set of propositions provided. All the propositions should work together in order to build a case for the proposed definition. As an author, I would be considered to accept all of those statements as true by default. [A] However, you as a reader would assign your own truth values to each and one of them. Finally, you would assign your verdict on the truthhood of H.

The first paragraph has already listed some propositions. We are on the right track. You probably have already assigned some rough truth values to all of those propositions. This would mean that the proposition A is true for you. [B] This kind of border check procedure takes place every time somebody presents us with some truth to be imported. The exact process is somewhat opaque. However, we can often observe how some truths seem to just pass through via a fast-lane as if they are citizens. Others might meet quite a bit of resistance together with some support. Their process is much lengthier and can take from seconds to months or even forever. They exist in a kind of quarantined area. We could say that their truth value is maybe. For example, the implicit proposition “H is true” at the moment is in the maybe state; it is still being evaluated. There are also truths that we outright reject. We might come around to them in later stages of our understanding of the world, but at present they receive the status of being false.

Where did the proposition B land for you? Would you say it is true? What arguments were for it to be true? How about for it to be false?

In my experience, the border check is always active when I read somebody’s argument. But I have already stated that. However, what I have not stated yet is that when I am in writer’s mode, the border screening is very much active too. Frankly, the whole process of writing could be summarized as throwing shit at the wall and seeing if it passes the border. The second paragraph is a good example of a paragraph that passed. But I did have to open the bags. For example, I started to wonder about the extreme cases like radical skeptics or trivialists. Do they operate in the described fashion? If we suppose that there actually is such a person that truly embodies a radical skeptic, for her, all knowledge is permanently quarantined. If we apply the same leeway for a trivialist, for him, every proposition is true. He has an open border policy. Thus, even in the extreme cases there appears to be a border and a procedure of dealing with inbound propositions. This reasoning was enough for me to keep the second paragraph. However, I should note that this sentence right here was added later during the revision of the paragraph; I realized that I am not completely confident using both “radical skeptic” or “trivialist” concepts in this context and I need a bit of a memory refresher [I should also not that the bolded text was also product of even further revision]; therefore the battle for the second paragraph was much more recursive then it would appear on the surface; suffice to say that the initial tension was resolved in favor of keeping those concepts1.

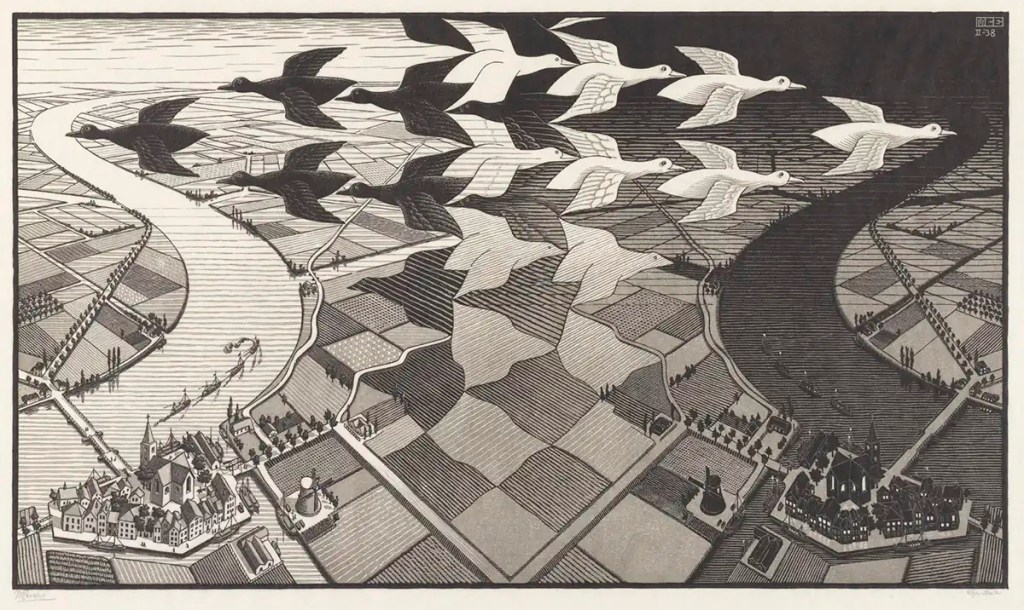

Personally, I find propositions that are in the maybe state to be the most interesting. Whether the proof is formal or informal, you still get to partially see the cogs of your truth making machinery turning. This emotional rollercoaster is eloquently depicted by Douglas Hofstadter2:

It is easy to imagine a reader starting at line 1 of this derivation ignorant of where it is to end up, and getting a sense of where it is going as he sees each new line. This would set up an inner tension, very much the tension in a piece of music caused by chord progressions that let know what the tonality is, without resolving. Arrival at line 28 confirms the reader’s intuition and gives him a momentary feeling of satisfaction while at the same time strengthening his drive to progress towards what he presumes is the true goal.

[…]

This is typical of the structure not only of formal derivations, but of informal proofs. The mathematician’s sense of tension is intimately related to his sense of beauty, and is what makes mathematics worthwhile doing.

Though we have not covered many topics, we did talk about them in a rather loopy fashion. A recap would do us good. First, we stated that every proof needs a set of propositions because otherwise how on Earth are we going to build an argument that would convince somebody that something is indeed true. Second, we have seen some of the propositions in favor of the definition of truth in question already. Some I hope you agreed with. Suppose you were convinced of all of them. Was this enough to convince you of H? Obviously, not. For one, the definition itself has not been stated yet. And two, should these kinds of defenses not be preceded by some background knowledge, perhaps including previously stated theories of truth?

Let us address the question of the background knowledge first. The most popular theory of truth in philosophical circles is the correspondence theory. It has some arguments for it that seem valid. It also has some criticism that also seems valid. In short, it has a set of arguments for it and a set of arguments against it. The definition of truth in correspondence theory is a proposition as well. We can state it here as “truth is correspondence to facts”. Aristotle, Descarte, Locke, Leibniz, Hume and many other great philosophers were advocates of this theory. It also has some opponents, namely the advocates of different theories of truth, such as deflationism or coherentism. If we were to present the theories of deflationists or coherentists, they would have the exact same form. Both of them would have some excellent arguments for them, usually at the expense of other theories. They would also have some great arguments against them. They too would have some famous philosophers as their proponents and opponents. There is a great count of other theories and even a greater count of their different flavors. However, to my knowledge, they all seem to follow this pattern. There is one final thing worth noting that is kind of loosely implied by the previous propositions, namely that amongst the philosophers even today there is no clear consensus which theory is right3.

Now that we have stated all the necessary background knowledge and presumably made some arguments for the definition, can we finally state it? Let us suppose I just did. I just stated what the H is. All of the propositions above were meant as empirical evidence for H. So far as you read those propositions you might have agreed with some or most of them. If you have not agreed with any of them, most likely you are no longer with us. However, you might be hesitant to agree that they prove H itself. You know what? Let us even assume you have some serious criticism, maybe you are a deflationist and truth is not a thing for you. Once you read that “the definition of truth is …” you already had one in the chamber ready to fire, and you immediately emailed me your argument against H. After reading the criticism, yours truly realized that there is indeed a problem. Upon further investigation, this author found it impossible to refute that there are instances where the definition fails. At this point the only way to save H would be reply saying that all of the truth theories face the exact predicament – my definition is no different. However this reply would be a strategic mistake. My counter-argument would be self-defeating, since it would appear that I promote pluralism. Therefore, my theory would simply collapse into just one more argument for the pluralist theory of truth. In addition, by sacrificing self-conviction I would render my definition to be inferior to all the other theories of truth.

It is a good thing I have not stated the definition yet. So far we just had a hypothetical discussion of some hypothetical definition of truth. I still have a card to throw, and the card is to define truth as a product of two opposing sets of truths. Not a pluralist anymore, instead of acknowledging that other definitions have the same flaw, I managed to fit everyone into the definition. However, I did something more here too. By acknowledging criticism as part of the truth nature, I have promoted this definition above others. Correspondence, coherence, deflationist theories, all have to live with the annoying neighbor called criticism, whilst the proposed definition invites it and turns it into an argument for it.

First question that might come to one’s mind is what is this product exactly? We have already seen few examples, but here are few more:

- A peace treaty between two countries.

- A verdict by a judge.

- A theorem that comes out of a proof.

- A memory recalled.

- A decision that was decided.

- Item #1 on this list.

- This list.

Instances of the word “product” here have many shapes, however they are all united by how they are forged. Namely, they are all results of a resolution of a tension that has once existed. More colloquially we could express the definition as truth is truce. We could also phrase it as truth is a product of criticism. This phrasing allows us to see what would happen if we were to construct a truth function based on this definition, and then feed the definition to this function. The proposed definition of truth would be a fixed point – even if somebody managed to provide any valid criticism, they would only be doing what the definition says would happen.

- This document itself was once called “A weird essay on truth” before it became “A weird essay on truth (V2)” – I felt that all of the paragraphs should reapply after being quarantined for two weeks.

↩︎ - Hofstadter, D. R. (1999). Gödel, Escher, Bach: an eternal golden braid. Basic books. ↩︎

- Based on a survey conducted in 2009, when faculty members from 99 leading philosophy departments were asked, ‘Truth: correspondence, deflationary, or epistemic?’, 50.8% answered correspondence,24.8% deflationary, 6.9% epistemic, and 17.5% other. (Bourget, D., & Chalmers, D. J. (2014). What do philosophers believe?. Philosophical studies, 170, 465-500) ↩︎